Hydra Part I - Matrix Mixer Framework

- Part I - Matrix Mixer Framework

- Part II - Hydra: The Model

Attention mechanisms

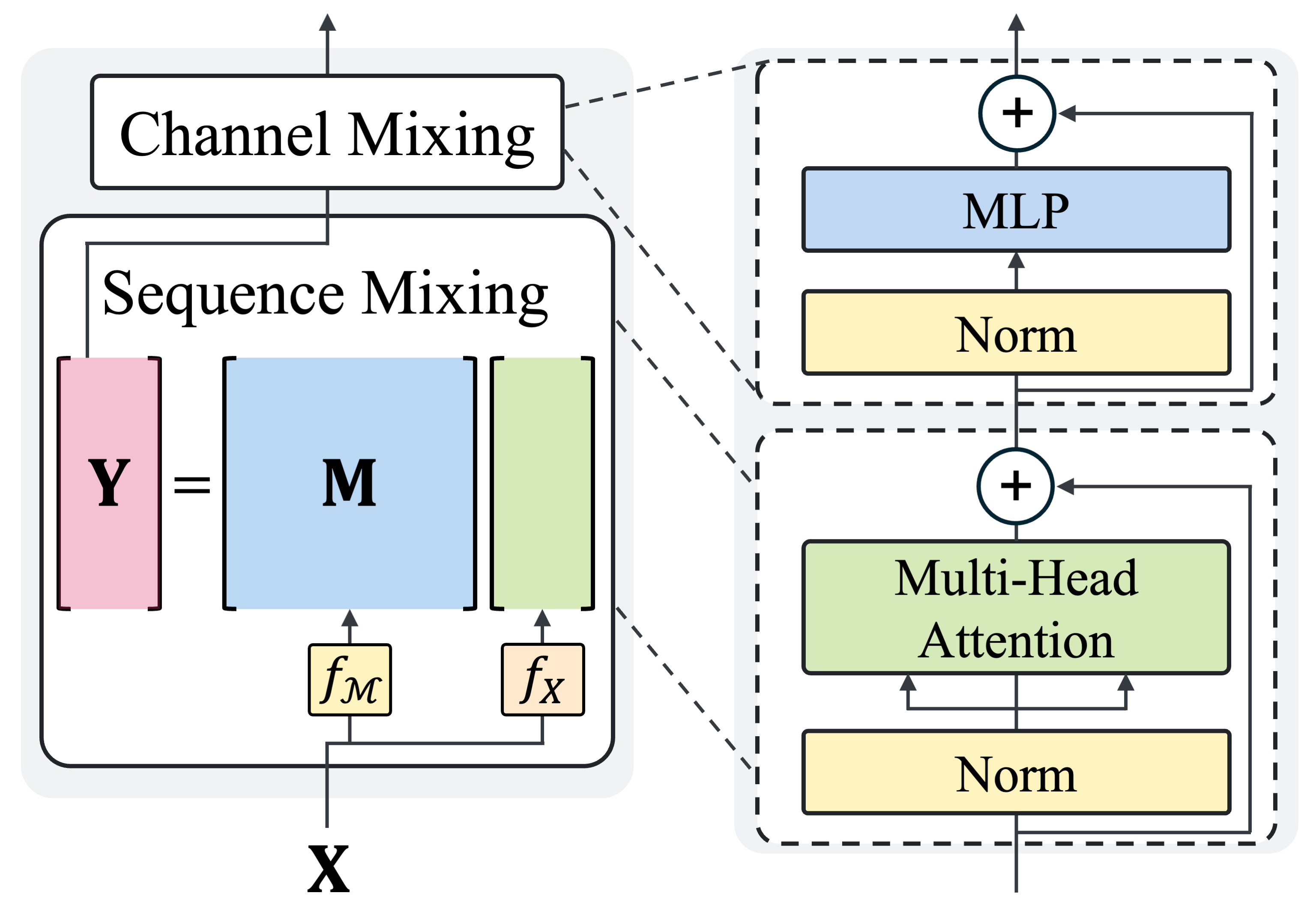

In modern state-of-the-art models, architectural designs typically split into two main components: the sequence mixer and the channel mixer. To illustrate, let’s look at the Transformer encoder architecture. It consists of two key elements: Multi-Head Attention and a Feed-Forward Network (FFN). The Multi-Head Attention serves as the sequence mixer, efficiently managing interactions across the input sequence. Meanwhile, the FFN acts as the channel mixer, processing information within each sequence element.

Take a glance at the figure below to see this architecture in action. You’ll notice how these components work together to create the robust models we rely on today.

In our work, we study the large and important class of sequence mixers that can be represented as basic matrix multiplications: $\textbf{Y} = \textbf{M}\textbf{X}$. We call this approach the matrix mixer framework. This framework includes diverse and important classes of sequence models such as Attention, convolutions

Viewing sequence mixers through this lens has a significant advantage: designing new sequence mixers becomes a matter of finding the optimal matrix $\textbf{M}$. This perspective opens up a systematic way to explore and innovate in the field of sequence modeling.

So, now the question is, what is a good $\textbf{M}$? Key desiderata for such a matrix would include:

- Efficiency: We want sub-quadratic matrix multiplication and parameterization to ensure our models run swiftly and handle long sequences with ease.

- Performance: The matrix mixer should match the high standards of Attention mechanisms in modeling diverse sequence data across various modalities.

- Flexibility: The solution should work well with sequences of different lengths (+ capable of both causal and bidirectional sequence modeling, which we will tackle in Part II)

Check out the table below to see how various sequence mixers measure up. While several models like MLP-Mixer

| Sub-quadratic | Performance | Flexibility | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLP-Mixer | 😭 | 😭 | 😭 |

| FNet | 🤗 | 😭 | 🤗 |

| TNN | 🤗 | 😭 | 🤗 |

| LA | 🤗 | 😭 | 🤗 |

| M2 | 🤗 | 😭 | 😭 |

| Transformer | 😭 | 🤗 | 🤗 |

As you can see, each of these models has its strengths and weaknesses, but none perfectly hit all the marks. This gap highlights the need for another approach in developing sequence mixers.

So, is it even possible to meet all three key criteria?

We believe the answer lies in examining the structures of the mixer matrix $\textbf{M}$. Our work begins with an in-depth theoretical and empirical analysis of various sequence mixers using the matrix mixer framework. We then extend this idea, offering a systematic approach to designing new sequence mixers. By fully leveraging this framework, we have developed multiple novel architectures, including a new bidirectional mixer named Hydra.

Let’s dive into more details, which is outlined as follows:

- We study and formalize the matrix mixer framework, introducing new theoretical concepts about structures of $\textbf{M}$ that can capture such desiderata.

- Guided by the properties of different matrix classes, we introduce a series of sequence models with strong and predictable performance.

- We provide careful systematic studies on these matrix classes, comparing empirical performances by varying only the matrix mixer

Formalization of the Matrix Mixer Framework

We begin by further formalizing our matrix mixer framework. While this framework can be applied to multi-head architectures, we will focus on the single-headed scenario here for simplicity.

In essence, a sequence mixer transforms an input $\textbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times C}$ into an output $\textbf{Y} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times C}$, where $L$ is the sequence length and $C$ is the number of channels.

- Input preprocessing function: Denoted as $f_X \colon \mathbb{R}^{L \times C} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{L \times D}$, this function handles common data transformations before the mixing process.

- Matrix construction function: Denoted as $f_{\mathcal{M}} \colon \mathbb{R}^{L \times C} \times \Theta \rightarrow \mathcal{M} \subseteq \mathbb{R}^{L \times L}$, this function maps input data to mixer matrices. Here, $\Theta$ represents the space of learnable parameters, and $\mathcal{M}$ represents the class of mixer matrices.

Given these functions, we denote the mixer matrix as $\textbf{M} = f_{\mathcal{M}}(\textbf{X}, \theta)$. The matrix mixer framework is then defined by the equation: \(\textbf{Y} = \textbf{M} (f_X(\textbf{X})).\)

Using this framework, we are now playing a game of finding the optimal $\textbf{M}$ that satisfies all three requirements: efficiency, performance, and flexibility! This systematic approach allows us to analyze the characteristics of different sequence mixers and formalize the properties needed to meet our criteria.

Let’s break down these objectives step-by-step and explore which matrices work best in achieving them.

Solution for Sub-quadratic Complexity: Structured Matrices

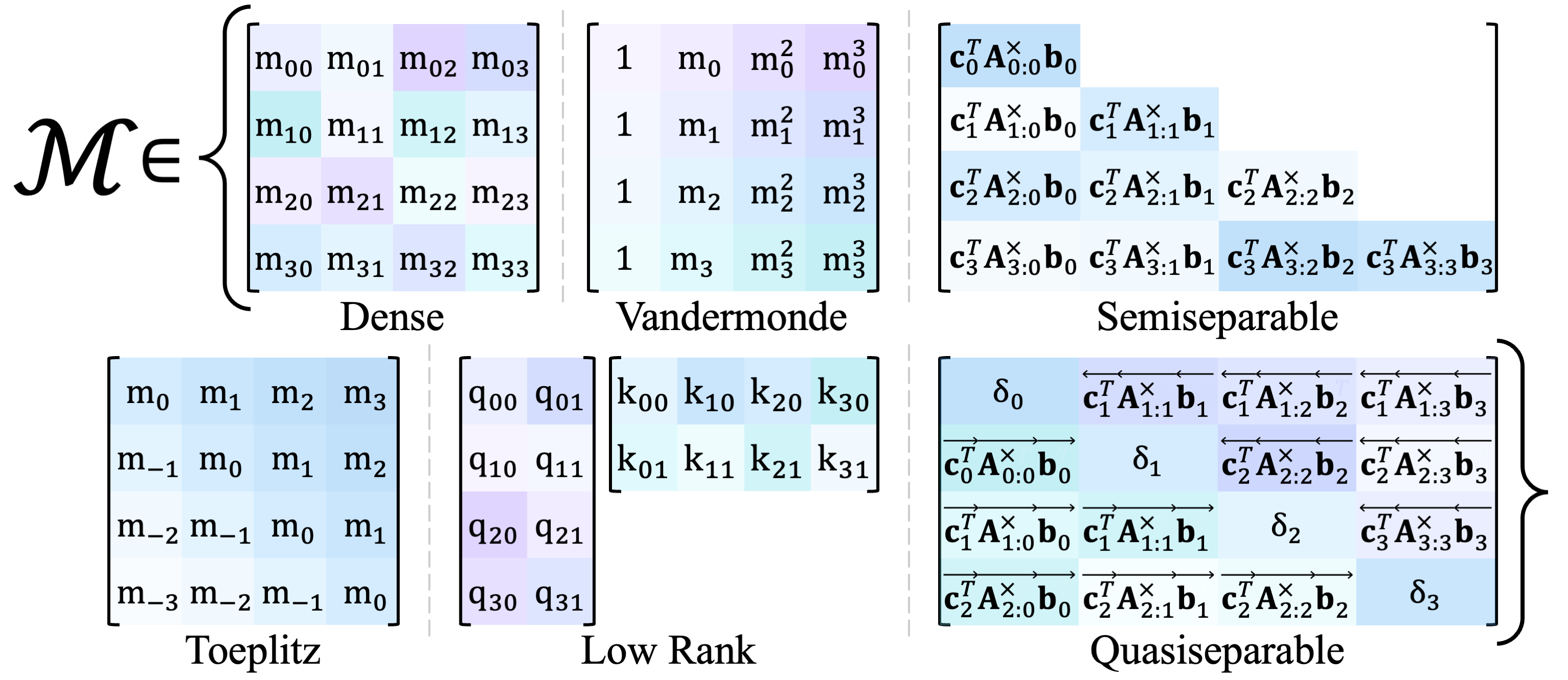

To meet our first key requirement – sub-quadratic matrix multiplication – we can focus on a special type of matrices known as structured matrices. For a general matrix $\textbf{M}$, matrix multiplication typically incurs a computational cost of $O(L^2)$. However, structured matrices, with their compressed representation, allow us to perform these operations much more efficiently, achieving sub-quadratic complexity. We refer to sequence mixers using these matrices as structured matrix mixers.

Structured matrices provide a broad array of options for our matrix mixer $\mathcal{M}$, as illustrated in the figure above. By leveraging these matrices, we can significantly reduce computational overhead while maintaining an efficient parameter count.

All previous versions of sub-quadratic sequence mixers fit within the matrix mixer framework. This categorization by the class of mixer matrices helps us systematically analyze and understand the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches.

Notations

Think of bold capital letters like $\textbf{X}$ as matrices, bold small letters like $\textbf{x}$ as vectors, and regular small letters like $x$ as scalars. When we talk about elements in a matrix, we’ll use subscripts. So, if we have a matrix $\textbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{M \times N}$, the element in the $i$-th row and $j$-th column is $x_{ij}$. If we’re looking at the whole $i$-th row, it’s $\textbf{x}_i$.

| Matrix Structure $\mathcal{M}$ | Formulation (\(𝑚_{ij}\)) | Complexity | Method Instantiations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dense | $m_{ij}$ | $O(L^2)$ | MLP-Mixer |

| Dense (Softmax Attention) | $\text{softmax}_j(q^T_i k_j)$ | $O(L^2)$ | Transformer |

| Low-rank (Linear Attention) | $q^T_i k_j$ | $O(L)$ | Linear Attention |

| Butterfly | Refer to | $O(L \log L)$ | Kaleidoscope |

| Toeplitz (Convolution) | $m_{j-i}$ | $O(L \log L)$ | S4 |

| Discrete Fourier Transform | $w^{ij}$ | $O(L \log^2 L)$ | FNet |

| Semiseparable | \(\textbf{c}^T_i \textbf{A}^{\times}_{i:j} \textbf{b}_j \mathbb{1}_{\{i \geq j\}}\) | $O(L)$ | Mamba (S6, SSD) |

As shown in the table above, using structured matrices (all but the dense variants) as the mixer matrix directly leads to sub-quadratic computational complexity.

Solution for All Desiderata: Sequence Aligned Matrices

So, can we simply choose any structured matrix as our sequence mixer matrix and expect it to meet all our requirements for efficiency, performance, and flexibility? Unfortunately, not all structured matrix mixers are up to the task. This begs the question: Is there a class of mixer matrices that can satisfy all three requirements? Fortunately, the answer is yes!

We introduce a special subset of structured matrices called Sequence Aligned Matrices (SAM). SAMs are designed to achieve efficiency, high performance, and flexibility all at once.

What are Sequence Aligned Matrices (SAM)?

In simple terms, SAMs ensure that the parameters for every submatrix $\textbf{M}[: i+1, : i+1]$ are only functions of the tokens up to index $i$. Here is a formal definition of SAM.

Formal definition of Sequence Alignment

Definition (Sequence Aligned Matrices) Let $L$ be the sequence length and let $\textbf{M} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times L}$ denote a matrix with a parameter set $\mathcal{P}$. Then, we say that $\textbf{M}$ is a Sequence Aligned Matrix if there exists a partition $\Pi$ of $\hat{\mathcal{P}} \subseteq \mathcal{P}$, and $\hat{\mathcal{P}} \neq \phi$, such that for all sets $\mathcal{E} \in \Pi$, there exists a bijective map $f_{\mathcal{E}} : [L] \rightarrow \mathcal{E}$, and, for each $i \in [L]$, the sub-matrix $\textbf{M}[:i+1,:i+1]$ is composed solely from the parameters in the subset $\cup_{\mathcal{E}, k \le i} f_{\mathcal{E}}(k) \subseteq \mathcal{P}$.

Properties of SAM

SAM matrices come with two crucial properties that make them stand out:

- Data Dependency: SAM matrices are dynamically generated from the input data. This means they adapt in real-time based on the information they process.

- Extendability: SAM matrices can handle inputs of arbitrary lengths, making them versatile for various applications.

Take, for instance, the Attention mechanism in Transformers. It’s a perfect example of a SAM matrix: the Query-Key-Value components are all dynamically projected from the input data, and the mechanism itself adapts seamlessly to different sequence lengths.

These two properties are not just nice-to-haves; they are essential for the flexibility and performance of modern models. Our experimental results strongly highlight the necessity of SAM, showing that SAM-based mixer matrices significantly enhance the performance of models.

SAM Variations

Let’s dive into a series of new SAM-based models we developed: Toeplitz, Cauchy, Vandermonde, and quasiseparable sequence mixers. By making these mixer matrices SAM, we achieved significant improvements. To make this explanation easier, we’ll assume that Query-Key-Value are projected from an input sequence.

Cauchy (Code)

We begin with our Cauchy variant, as it shares a significant similarity with the Attention mechanism: the norm of $m_{ij}$ represents the magnitude of correlations between the $i$-th and $j$-th tokens. Following the definition of Cauchy matrices, our SAM Cauchy mixer works as follows:

\[\begin{equation} \textbf{Y} = \textbf{M}\textbf{V}, \qquad \qquad m_{ij} = \sum_{d} \frac{1}{(q_{id} - k_{jd} + c)} \space, \end{equation}\]where $\textbf{Q}, \textbf{K} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times D}$, and $\textbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times C}$ are projected matrices from $\textbf{X}$, and $c$ is a trainable constant that stabilizes training by preventing divide-by-zero errors.

Vandermonde (Code)

Recall the definition of Vandermonde matrices: $m_{rs} = (m_r)^s$. Due to the exponential values, this can lead to instability during training. Therefore, we use the formulation $q_{rs} = \mathfrak{R}(e^{i \cdot r \cdot q_s})$ and $k_{rs} = \mathfrak{R}(e^{i \cdot s \cdot k_r})$ for $\textbf{Q}$ and $\textbf{K}$. This technique, taking the real part of complex numbers, is commonly used in SSMs. Under the same setting as our SAM Cauchy mixer, our SAM Vandermonde mixer $\textbf{M}$ is parameterized as:

\[\begin{equation} \textbf{Y} = \textbf{M}\textbf{V}, \qquad \qquad m_{ij} = \sum_{d}(\cos(2 \pi q_{id}^j) - \cos(2 \pi k_{jd}^i)) \space, \end{equation}\]where the cosine function comes from Euler’s formula.

Toeplitz (Code)

A Toeplitz matrix mixer is inherently a convolution between weights $\textbf{w} \in \mathbb{R}^{2L-1}$ and an input sequence $\textbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times C}$. Usually, a general convolution adopts input-independent $\textbf{w}$, which does not satisfy the definition of SAM. Therefore, we extend our Toeplitz matrix mixer to be SAM as follows:

\[\begin{equation} \textbf{Y} = \mathcal{F}^{-1}(\mathcal{F}_\textbf{w} \odot \mathcal{F}_\textbf{V}), \qquad \qquad \textbf{w}_{i} = \begin{cases} q_{i-L+1} & \text{if } i \geq L \\ k_{L-i+1} & \text{if } i \lt L \\ \end{cases} \space , \end{equation}\]where the convolution is implemented using FFT $\mathcal{F}$, and $\textbf{q}, \textbf{k} \in \mathbb{R}^{L}$ and $\textbf{V} \in \mathbb{R}^{L \times C}$ are projected from $\textbf{X}$.

Quasiseparable (Code)

This variant has a separate name, Hydra. Stay tuned for Part II 🤭

Impact of SAM Parameterization

Now, we validate that the SAM matrix mixers are better than non-SAM mixers. To prove this claim, we conducted strictly controlled systematic albations where the only variable was the mixer matrix. Check out our efforts for a comprehensive and fair comparison!

| Structure | Data Dependent | # Params | GLUE Avg | Δ |

| Dense | ❌ | 71M | 74.7 | |

| Toeplitz | ❌ | 71M | 75.8 | +1.9 |

| ✅ | 72M | 77.7 | ||

| DFT | ❌ | 71M | 71.7 | +5.2 |

| Vandermonde | ❌ | 71M | 70.8 | |

| ✅ | 70M | 76.0 | ||

| Cauchy | ❌ | 71M | 74.2 | +4.0 |

| ✅ | 70M | 78.2 | ||

| Low-rank | ❌ | 71M | 74.9 | +3.5 |

| ✅ | 70M | 78.4 | ||

| Attention | ❌ | 71M | 71.9 | +6.9 |

| ✅ | 70M | 78.8 | ||

| Quasiseparable | ❌ | 72M | 75.1 | +4.6 |

| ✅ | 71M | 79.7 |

The results in the table above clearly demonstrate the importance of SAM. Regardless of the matrix class, incorporating the SAM property always leads to a significant performance boost. Additionally, our SAM-based Toeplitz, Cauchy, and low-rank mixers perform remarkably well, with quasiseparable mixers even surpassing Attention. These findings underscore the immense potential of structured matrix mixers as efficient yet powerful sequence mixers.

Next Up

Curious about the quasiseparable matrix mixer? In the next part, we’ll introduce Hydra, our bidirectional extension of SSMs that not only surpasses Attention but also achieves sub-quadratic complexity. Stay tuned!